Part II: The Stress of Shoto Todoroki: Somaesthetics and Adverse Childhood Experiences

The home you come from is just like the zip code you live in-- it determines so much about a child's future as an adult.

Hi, hello,

So, your parents and the dynamics at home growing up were traumatizing. Welcome; there are cran-grape and caviar in the back—call it Cozy Communion.

You are seen, safe, and belong here. Now, sit down and let’s chat.

You’ve been searching for a way to move forward, but you don’t know how to release the fear and shame of the version of yourself you could’ve been if your life had been different if that Thing hadn’t happened, or if those people had sought their own healing and development. You want to let go of those nagging, gnawing memories that haunt you awake at night.

But you can’t.

For some reason, you can’t let go even though you want to, even though your soul is begging to grow beyond the pain, and you don’t know what to do.

I get it. I’ve lived it and still think about how different I would be if I had a better paternal parent. Everyday somaesthetics as embodied healing: the balance between hurt and harmony is a matter of the heart. So, let’s talk about it so that we can heal from it together. Let me help you better understand what’s going on in your mind, body, soul, and spirit.

The balance between healing, hurt, and harmony is a matter of the heart.

Everyday Somaesthetics as Embodied Healing

I love reading and writing because they are the only two crafts that my parents had no control over. Every time I tried to venture into something else I wanted to do—the saxophone, video games, dance, basketball, soccer—I was always told no for arbitrary reasons (sexism and gender bias, not wanting to pay or pick me up, not wanting me to get hurt, needing me to raise my sisters) that, looking back, deeply impacted my personal and creative development. If it wasn’t academically related, they could not see me in it, let alone support my interest, and even then, the support wasn’t for too long.

I don’t think I’m unique in this experience in general, but in my household, my experience was very different than my siblings’ ability to explore their kinetic, musical, and visual interests. They were allowed to play, dance, run, march, be active. But I had my books, I had my journals, I had my pencils and pen, and my imagination within all my stress and solitude. I used them to vent and escape a really difficult childhood.

The process of decolonizing our spirit-minds and bodies from an ableist-imperialist-white supremacist patriarchal culture is deep spiritual work. As a multiply-neurodivergent and marginalized gender of immigrant Nigerian heritage and Black American lived experiences, I conceived of the Everyday Somaesthetic framework as a means of creatively and critically engaging with the work of healing soul wounds through embodied storytelling.

The balance between healing, hurt, and harmony is a matter of the heart. Embodying and enacting change requires greater mental, emotional, and physical intentionality. It requires unlearning the programming of our systems of oppression and relearning how to fight and pursue our liberation. This is why making informed life choices—surviving, flourishing, and thriving—can be challenging, especially in times of crisis and hardship. Living is taxing on the body, mind, and spirit.

When you introduce life’s natural stressors and dysfunctional family dynamics into the mix—making life-altering decisions such as cutting off contact with an abusive parent, escaping a conflict-affected area with family or alone, or opting for peacebuilding actions amidst the chaos that war and conflict wreak upon the fabric of society—it becomes evident that the intersections of our inner lives with the material conditions and sociopolitical factors affecting individuals (including social identities, marginalized and privileged statuses, socioeconomic status, migration status, and various experiential circumstances all play a role in shaping our daily experiences.

In a critical analysis of how to “guide counselors working with Native Peoples,” Duran (2006) defines soul wounds as resulting from “a legacy of cultural trauma, ungrieved losses, internalized oppression, and learned helplessness. Comas-Diaz (2012) asserts that soul wounds are “a response to cultural and spiritual hegemony.” This author pushes Comas-Dias’ thinking further: soul wounds are the byproducts of being Othered across racial, gender, class, and (dis)ability lines as a means of spiritual and mental warfare of the white dominant-capitalist-patriarchal culture against our psycho-spiritual roots. But soul wounds almost always start at home when we are children with our parents or primary caregivers.

I coined Everyday Somaesthetics—the everyday spiritual, emotional, mental, and aesthetic choices a neurodivergent and other marginalized person makes to lead an integrated life—as an interdisciplinary, neuroqueer,1 and neurospiritual pedagogical framework2 to explore soul wounds from adverse childhood experiences into adulthood outside of religious confines.3

It is how I approach my spiritual guidance practice at The Sol Gospel.

In an in-depth interview with Coleen Kraft, a physician and president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, journalist Kristine Phillips reported,

“Such a situation could have long-term, devastating effects on young children, who are likely to develop what is called toxic stress in their brain once separated from caregivers or parents they trusted. It disrupts a child's brain development and increases the levels of fight-or-flight hormones in their bodies, Kraft said. This kind of emotional trauma could eventually lead to health problems, such as heart disease and substance abuse disorders.”

This highlights that the sum of our individual and collective daily choices makes up our lives, societies, and world. Moments in our actions reveal the essence of our choices. One's daily aesthetic choices and experiences play a crucial role in survival and the capacity to continue living. It is a privilege to choose and dictate how each day unfolds and how one’s life ultimately develops on a larger scale, and a delicate balance must be struck to embody a somaesthetic politic that leads to growth rather than destruction of the self and our environment. This is no better exemplified in anime than through the character development of Shoto Todoroki from My Hero Academia.

The Somaesthetics of Shoto Todoroki

I love discussing aesthetic philosophy with Shoto, and you can read my first newsletter writeup on him here. When I wrote "Fire and Ice: Struggle as an Aesthetic Experience,” season 7 of My Hero Academia was still building itself up, and Shoto’s family and character development arc had yet to shine forth. But SO MUCH time has passed, the season is done, as is the manga series, and the final season of the anime premieres this October. So, I have seen things! The things I have seen about “The Hellish Todoroki Family” morally and philosophically center Shoto’s spiritual, physical, emotional, and character development.

To talk about the effects stress has on children, we have to mention the role that abusive and absentee parents play. Money, affluence, and even poverty don’t have the same impact on a child’s mental health (and illness), socialization, and personal development as their exposure to parenting.

Every child experiences a unique version of their parent(s). Each sibling has a different perspective and narrative of their parent(s). Every parent establishes the standard for how their children treat them and each other. The way parents treat their children can significantly influence how siblings interact, either stressing or strengthening their sibling bonds. Assemble all the shattered pieces like stained glass and you’ll form a mosaic representing both the parent and the child’s relationships within the family system and with those outside of that, for better or for worse.

Stress originates from our bodily experiences. Factors that create stress—such as people, places, or events—only transform into stressors when the mind interprets them as such, prompting a physical reaction.

Despite being the prodigious fourth child and the youngest son of Endeavor (the former No. 2 and current No. 1 Pro Hero in Japan’s Hero Society), Shoto’s backstory and family life are filled with tragedy and pain— the death of an older sibling, a violent and emotionally abusive patriarch wielding power and prestige; a mother struggling with mental illness onset by domestic violence, the misdirected anger that often falls on a child as a result, and the literal, permanent scars such abuse leaves.

Additionally, there is his ostracism from his three older “imperfect” siblings and a lack of emotional intimacy and loving physical touch. I could go on, but know that my boy had it tough. Once he realized he would never be strong enough to surpass his rival, All Might, Endeavor’s life’s goal became creating a child whose Quirk (superpower) would surpass All Might to become the number one hero in Japan and the world. And it backfired big time.

Endeavor’s Quirk is Hellflame, and indeed, the man behind the Pro Hero, Enji Todoroki, made his family’s lives a living hell. Everyone suffered greatly in their distinct ways, but Shoto had to bear the weight of his father’s misguided fanatical endeavors and be the son to suffer the father's sins to save his family, Japan, and Hero Society.

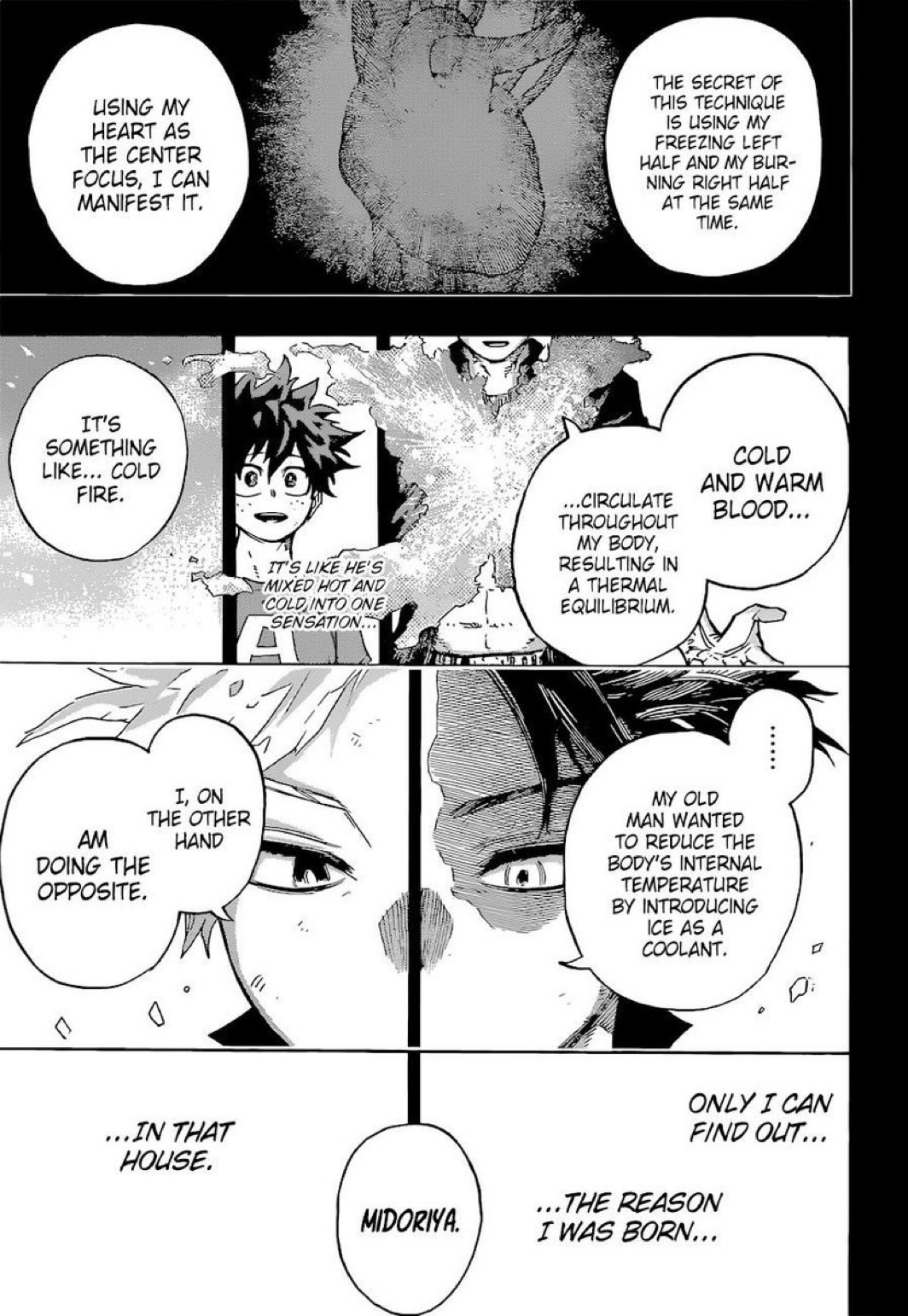

He develops an Ultimate Move: Phosphor, Flashfire Fist: Phosphor, using his Half-Cold Half-Hot Quirk and his estranged eldest brother’s Quirk, Blueflame, respectively.

“Our father was a madman! Our family was a nightmare!

Even so, you’re the only one of us who chose to burn people!”

Shoto to Dabi, e146 - Two Flashfires

Fire and Ice Working in Harmony

Phosphor allows Shoto to channel both halves of his Quirk throughout his body via his circulatory system. He uses his heart as a generator to circulate the chilled and hot blood around his entire body, merging the two halves of his Quirk into a single ability. By putting his heart and body in “a state of balance

and listening to a friend who cares, Shoto discovers the truth: this is his Quirk.

His father sought an Ice power that would regulate the heat of a fire Quirk— a guardrail, not an equalizer. In a sense, Endeavor wanted Shoto to always be at war with himself. However, he chose a different path; it was the only way he could accept himself despite the real reason for his birth. Shoto describes this as his body coming together "as one" and creating "a body even Dabi can't burn."

The move gives Shoto an incredible defensive and offensive advantage against most opponents, especially those with pyrokinetic Quirks. The flames generated by the technique are described as "Cold Flame," allowing him to burn and freeze his opponents simultaneously. It’s unfortunate that once he finds this internal balance, he must use it to defeat his brother—the same brother who inspired Phosphor—whose resentment for their father has turned him into a villainous ticking time bomb.

Emotional Equilibrium: Balancing Two Halves of a Whole Human

and a Split Heart

Dabi is the elder brother who was previously believed to be dead but is actually estranged. Dabi, whose real name is Toya Todoroki, became a villain due to his father’s rejection. As the firstborn, Toya loved his father and desperately wanted to be the child who followed in his father’s footsteps with the fire Quirk, fulfilling Endeavor’s dreams of surpassing All Might. Toya’s motives were corrupted by the insecurity imposed upon him, and Endeavor turned him away because he could not control his fire as he had hoped a child would, like Shoto.

Consequently, Endeavor considered Toya a failure or a lost cause. From that moment on, after discovering that Shoto was the “Chosen One,” resentment and envy grew in Toya’s heart toward baby Shoto, leading to violent outbursts fueled by feelings of rejection and being replaced by his father's affection. Then, tragedy struck. Dabi burns to death in a forest, waiting for his father to watch him train his fire Quirk, and the lives of the Hellish Todoroki family are forever changed.

More than a decade later, Dabi returns seemingly from out of the grave to seek revenge on Endeavor for making his life a living hell, and he’s prepared to kill anyone (and has), including his younger brother Shoto, to accomplish this.

Becoming his older brother’s anathema, his most suitable opponent, and a mirror reflection of what was, what could have been, and what will never be due to childhood trauma, Shoto urges his brother to let go of all his pain because he understands Toya is suffering.

“Focus your anger on me. I can handle your flames. Give me everything you’ve got. Maybe that’ll help you cool your head!”

Just one look at Dabi’s patchwork-stitched burnt face and body shows how much trauma his body stored. The way he crashes out reveals how much trauma his brain held for so long. The way he screams and thrashes and cries proves how much damage has been done and how much love and healing he needs to be restored. But Dabi’s body is burnt to crisps, and his heart is broken even as it’s frozen in time.

So, Shoto decides to battle his older brother, to share in their father’s burden to repair the family he ruptured, to confront his family’s demons and become the hero he desires to be; he does not turn away from the family dysfunction; he runs towards it to bring balance and healing. To save his family.

And he wins. In the end, Shoto comes out on top.

But the road to recovery in mind, body, and spirit for Shoto doesn’t end there. In fact, for the entire Todoroki family, the healing journey is just beginning.

But Shoto has the tools to heal now. He understands how his emotions affect him and, therein, his Quirk. Most importantly, he has friends to help him get through and grow from this. It’s his friendships that got him this far.

The Somaesthetics of Making Friends

In the final installment of this somaesthetic series, I will explore the somaesthetics of sensing stress and making friends to transmute it.

Students learn how to process complicated feelings and respond morally and ethically, as demonstrated by creativity, courage, collaboration, and resilience. Through engaging with visual and creative arts from diverse and multicultural perspectives, students can learn history, sociology, class and gender politics, and even new languages. The best way for a child and an adult to do that is by making genuine friendships with even one person who wants to understand them without the performance mask of a professional hero. Only human.